Local Information

Mission Bay Origins and the San Diego River

The San Diego River begins in the Cuyamaca Mountains northwest of the town of Julian. The river travels just 52 miles from its origins to where it meets the ocean. From the Cuyamaca mountains which contain Lake Cuyamaca (our first and highest elevation reservoir), the water reaches El Capitan Reservoir, the largest reservoir in the watershed. From El Capitan Reservoir, the river runs through Santee, and then one of the largest urban parks in America, Mission Trails Regional Park in Tierrasanta. After Tierrasanta the river generally flows through Mission Gorge and along the Interstate 8 where it and the freeway both end around Mission Bay and then Ocean.

The San Diego River begins in the Cuyamaca Mountains northwest of the town of Julian. The river travels just 52 miles from its origins to where it meets the ocean. From the Cuyamaca mountains which contain Lake Cuyamaca (our first and highest elevation reservoir), the water reaches El Capitan Reservoir, the largest reservoir in the watershed. From El Capitan Reservoir, the river runs through Santee, and then one of the largest urban parks in America, Mission Trails Regional Park in Tierrasanta. After Tierrasanta the river generally flows through Mission Gorge and along the Interstate 8 where it and the freeway both end around Mission Bay and then Ocean.

Mission Bay Park was developed from the 1940s through the 1960s. It was originally named “False Bay” by Juan Cabrillo in 1542 when the Spanish were exploring places to moor their ships. Over time, until 1852 the San Diego River has shifted where it meets the ocean from San Diego Bay to “False Bay” (Mission Bay) at least a few times; usually as a result of unusual rainfall or drought periods. In 1852 the United States Army constructed the first dike to keep it from shifting back to San Diego Bay. This construction solidified “False Bay” as the estuary that would drain the San Diego River. The original dike did fail, but also lead to the eventual flood control channel that we have today. In the late 19th century recreational development begain in “False Bay”.

To help diversify the city’s economy from primarily military, a Chamber of Commerce committee recommended developing Mission Bay into a tourist and recreational center in 1944. Over the next half of a decade, operations moved 25 million cubic yards of sand and silt from this marshy area to create the landforms of Mission Bay Park.

Today, the San Diego River is flanked on both sides by flood control levees that constrain it to the ocean alongside Mission Bay and between the South jetty of the bay’s entrance and Ocean Beach.

Mission Beach

Where Mission Bay’s jetties meet the Pacific Ocean, they are framed by the San Diego River along the Southern jetty and Mission Beach along the Northern jetty. Mission Beach wasn’t created entirely during the above mentioned dredging project, but it was definitely shaped and enhanced.

Where Mission Bay’s jetties meet the Pacific Ocean, they are framed by the San Diego River along the Southern jetty and Mission Beach along the Northern jetty. Mission Beach wasn’t created entirely during the above mentioned dredging project, but it was definitely shaped and enhanced.

During the dredging project that created Mission Bay from “False Bay”, the sandbar between the Pacific Ocean and Mission Bay was increased. Mission Beach spans almost two miles along the ocean and includes a boardwalk the entire way; extending into Pacific Beach to the North. The peninsula-like area of sand between the bay and the ocean has been coined “South Mission” and towards the North; “North Mission”. The “Sound Mission”area terminates at the jetty entrance with plenty of grass and parking and walking/biking areas.

Interesting to note is that many residential structures in Mission Beach were built in the 1930s and ’40s as summer cottages and some date as early as the 1920s. Ocean Beach to the South and Pacific Beach to the North, both developed earlier than Mission Beach because of issues dealing with how to develop on the sand that had been dredged to create this acreage. Because of a developing real estate market in those adjacent areas and a wooden bridge linking Mission Beach and Ocean Beach, a new subdivision was made official in 1914. John D. Spreckels had a large amount of land in this subdivision and sold them and parsed out as many small lots. As a result, Mission Beach is the most densely developed residential community in San Diego. It also has the smallest lots in the city, ranging from 1,250 square feet to 2,400 square feet. The wooden bridge to Ocean Beach was closed to traffic in 1950 and demolished in 1951.

Today, Mission Beach hosts many of our annual beach tourists. Mission Beach hosts the most short term vacation rental properties of any region of the city and has quite the night-life scene as well.

Pacific Beach

Pacific Beach, or PB as it is usually referred to in San Diego is bound by Mission Beach to the South, and La Jolla to the North. Initially PB was mostly populated by young surfers and college students, but like a lot of coastal Southern California, because of rising property values and therefore rent, the population is gradually aging and shifting to the more affluent. PB definitely has some of the city’s most developed night-life environments. PB hosts a variety of places to eat, drink, shop and play.

Pacific Beach, or PB as it is usually referred to in San Diego is bound by Mission Beach to the South, and La Jolla to the North. Initially PB was mostly populated by young surfers and college students, but like a lot of coastal Southern California, because of rising property values and therefore rent, the population is gradually aging and shifting to the more affluent. PB definitely has some of the city’s most developed night-life environments. PB hosts a variety of places to eat, drink, shop and play.

As with many California cities of the day, the history of San Diego’s development can be traced to the completion of a west bound railroad in 1885. San Diego then boomed to life in the late 1880s. A railway connected PB and downtown San Diego in 1889; it was extended to Pacific Beach’s Northern neighbor, La Jolla, in 1894.

From 1887 to 1891 Pacific Beach was called home by an asbestos factory, a race track and the San Diego College of Letters; none of which are around today. Around 1900, much of the land in Pacific Beach was used for growing citrus. At the base of Garnet Ave, PB has one of its most iconic landmarks, Crystal Pier, which opened in 1927. In 1943, the Roxy Movie Theater opened and catered to a Pacific Beach population that grew fivefold during WWII. A wave of currently established hotels then opened, including: The Bahia (1953), The Catamaran (1959), and Vacation Village (1965).

Ocean front lots sold for between $350 and $700 in 1902. By 1950, the population of Pacific Beach reached 30,000 and the average home sold for $12,000. Nonetheless, a small number of farms remained. Today, homes can sell for millions.

During the 1960s, development continued to increase with the city’s investment in Mission Bay Park, including the developments of the Islandia, Vacation Village and Hilton Hotels. In 1964 Sea World opened, which is located only a few miles from Pacific Beach.

It was during this time that Seaforth Sportfishing was established. Originally Seaforth Sportfishing was located down the current street, closer to the Hyatt Hotel.

Kelp Beds

As you leave Mission Bay and enter the Pacific Ocean you will be welcomed by kelp. We refer to the areas of kelp as ‘kelp forests’, ‘the kelp beds’ and/or the ‘kelp line’. The kelp beds generally form parallel to the coast because they live in a specific range of depth and grow off of a rocky bottom. The kelp cannot grow in sandy areas, for it has nothing to use as a strong-hold. The kelp beds grow in water that generally ranges in depth from 25-125 feet. “Kelps” are a class of brown algae that can grow to large sizes. They are attached to the ocean bottom, and many have flotation devices to buoy themselves to the water’s surface.

As you leave Mission Bay and enter the Pacific Ocean you will be welcomed by kelp. We refer to the areas of kelp as ‘kelp forests’, ‘the kelp beds’ and/or the ‘kelp line’. The kelp beds generally form parallel to the coast because they live in a specific range of depth and grow off of a rocky bottom. The kelp cannot grow in sandy areas, for it has nothing to use as a strong-hold. The kelp beds grow in water that generally ranges in depth from 25-125 feet. “Kelps” are a class of brown algae that can grow to large sizes. They are attached to the ocean bottom, and many have flotation devices to buoy themselves to the water’s surface.

Kelp forests are particularly appreciated for their high productivity and diversity. These thriving communities harbor an amazing variety of organisms. Because of the high productivity of these algae (kelps), the number of microhabitats shelter more than 150 species of invertebrates seeking hiding places, food and living space. Other organisms live on the blades (analogous to leaves) and stipes (analogous to stems) of the kelp in different depths of the water column. Other animals shelter and hunt near the kelp. The net result is that more than 800 species have been identified in and around kelp forest communities of southern California.

We often see a lot of our Southbound California Gray Whales extremely close to the kelp forests; sometimes even in the kelp. Although the Gray Whales are known to not particularly eat on their great migration; they have also been seen taking advantage of meals on the go. Because the kelp beds offer such a biodiversity, there are probably many reasons that the whales tend to stay close to the kelp line, whether it be food, protection or directional assistance.

La Jolla / Children’s Pool

La Jolla, just north of Pacific Beach, is an area of mixed geology, including sandy beaches and rocky shorelines.

Mount Soledad is covered with the narrow roads that follow its contours and hundreds of homes overlooking the ocean on its slopes. It is the home of the large concrete Mount Soledad Easter Cross built in 1954, later designated a Korean War Memorial.

The most compelling geographical highlight of La Jolla is its oceanfront, with alternating rugged and sandy coastline that serves as habitat for many wild seal congregations. One very popular and often controversial Pinniped viewing spot is ‘Children’s Pool’. An internet search for ‘Children’s Pool, La Jolla’ will provide lots of interesting news articles and opinions on this topic.

Children’s Pool Beach is a small sandy beach area located at 850 Coast Boulevard, at the end of Jenner Street. The Children’s Pool earned its name after the construction of a concrete breakwater in 1931. The structure was gifted to the community of La Jolla by the local philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps, who paid for the construction of a breakwater project in order to create a place where children could play and swim that would be protected from waves.

The first mention by the city council of seals in the area was in 1992, when it was noted that the population of marine mammals and particularly harbor seals had been increasing over the past 10 years. In November 1994 the city created a Marine Mammal Reserve. The Reserve was created for a 5-year period and later renewed for a second 5-year period. The boundary of the reserve extended almost to the seaward entrance to Children’s Pool. State agencies expressed conflicting opinions about the legal ability of the city to create this reserve.

By 1996 twice as many seals were using the beach as were using nearby rocks. Seal pup births were observed at Children’s Pool for the first time in 1999. The NMFS attributed the change to the increase in the local seal population, an increase which had been observed throughout the West Coast.

In September 1997 the city closed Children’s Pool to swimming because of “continuously high fecal coliform counts”. The high bacterial count was later confirmed to be caused by “a seal excrement overload”. At that time a discussion began about whether the seals should be removed from the Children’s Pool beach. A controversy developed over the purpose of the beach. Some wanted it to be treated as a marine mammal sanctuary, while others wanted to preserve it for recreational swimming. The California Coastal Commission ruled that Children’s Pool cannot be used as a marine preserve and must remain open to public access. In February 2000, the National Marine Fisheries Service said it intended to manage the area as a “harbor seal natural haul-out and rookery”. In February 2003 the NMFS told the city it could not intentionally harass the seals at Children’s Pool in order to remove them but could undertake activities that might temporarily displace the seals such as a dredging project to improve the water quality at Children’s Pool. In 2004 the NMFS said the matter was “a local issue for the city to resolve” and that the city can remove seals it considers a nuisance.

As of late 2009, about 200 harbor seals were using the beach regularly. The seals have become a popular tourist attraction.

La Jolla Canyon and Scripps Canyon

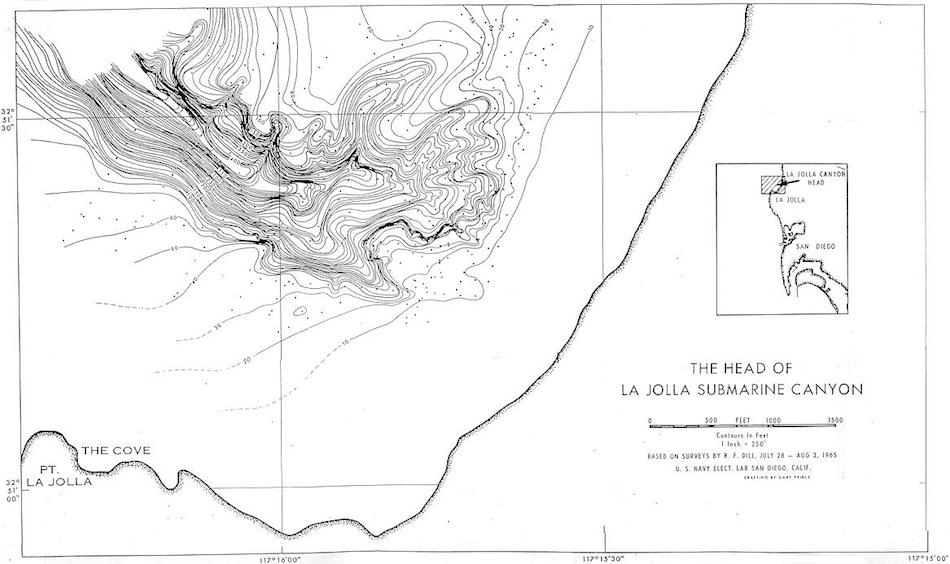

*Image courtesy of PV Lab – Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

*Image courtesy of PV Lab – Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute

Consisting of three branches — North, Sumner, and South — Scripps Canyon is approximately one mile long. The three separate branches are considered incised land canyons, as they extend into the coastal cliffs. The walls of Scripps Canyon are incredibly narrow, and in some places are so close together that anything that would normally sink is incapable of doing so. In some areas, the canyon features rocky, overhanging walls, which display signs of erosion, such as scoured and grooved surfaces.

At the head of La Jolla Canyon, there are a series of gullies that include semi-consolidated Pleistocene mud. This mud is home to many invertebrates that burrow and bore into it. Although La Jolla Canyon is wider than Scripps Canyon, there is a wide bowl and narrow rock gorge with steep walls that can be entered at 400 feet, near the head of the canyon. Lower down, Eocene and Cretaceous rocks are also incorporated into La Jolla Canyon.

The La Jolla and Scripps Submarine Canyons mark the end of the Oceanside Littoral Cell, which begins in Dana Point. A littoral cell is a section of coastline where wave energy disperses, creating a complete cycle that moves sand on and off the beaches (known as a sedimentation cycle). This area extends along the coast, bordered by the beach on one side and ending just beyond where the waves break. Sediments, driftwood, and other plant debris are carried south along the Oceanside Littoral Cell, as well as any garbage that has gotten into the water. These currents can sometimes be rapidly moving, further eroding the walls and floors of the canyons. Both Scripps Canyon and La Jolla Canyon feature large detrital mats of surfgrass and kelp. These mats are home to a dense natural macrofaunal community that when combined, is unmatched in magnitude anywhere else in the world.

At a depth of approximately 900 feet, Scripps Canyon and La Jolla Canyon meet and continue on into the ocean as a rock-walled canyon. At about 1,600 feet deep, the canyons meet a fan valley, which is cut into unconsolidated sediment. Along the axes of both canyons, there are a series of steps. Some of these steps have rock lips and a vertical drop of at least ten feet, while other steps consist of steep sediment-covered slopes that are only a few feet high, likely indicating landslide scarring.

The La Jolla Canyon empties into the San Diego Trough via a submarine fan, which is creased by a steep-sided valley that veers to the south. Throughout the right bank of the valley, complex natural levees can be found. These levees are poorly developed along the left side, with the exception of the outer third. In the central portion (adjacent to the inner channel), there are well-developed terraces, which are much more discreet along the outer valley and found at intermittent and variable heights in the middle portion. There may be some remnants of distributaries along the outer part of the valley, but there is nothing distinct overall. Along the outside of the winding bends of the channel, there are precipitous walls that are currently experiencing active slumping. As a result, it is common to find large slump blocks of clay along the floor.

This very geological diverse section of our cruising area offers a great opportunity of biodiversity. With depths of 0-1000 feet in such a small area, we often see just about every kind of sea life available in our region right here around the canyons. It truly is a unique location. Click here to view the local underwater geography in greater detail.

9 Mile Bank

The nine mile bank stretches approximately 10 miles NW to SE and is roughly 14 miles from our location on a 220 degree heading from Mission Bay to the top of the 9 Mile Bank. It is an underwater mountain range that gets as shallow as 330 ft.

The nine mile bank is usually a treasure box of life. Although it’s not that far from land, it is still far enough that it can be very independent of weather and local influences of our local water closer to land. Oftentimes a rainstorm or sudden warming of our local water near land can produce green water or algae blooms while the 9 mile bank has plenty of room for that water to ‘clean up’ and become a nice purplish blue.

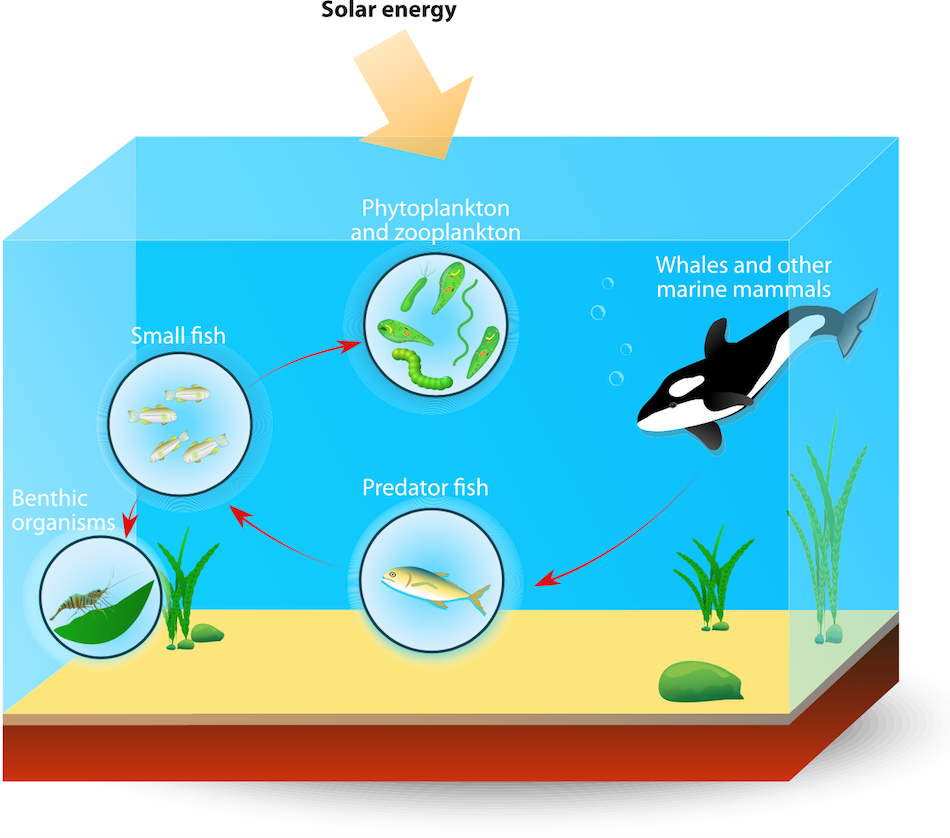

Banks, ridges, or underwater mountain ranges often provide a great place for marine life to gather because the deep currents will collide with the sides of the bank and create an upwelling. This upwelling brings nutrients and plankton from the deeps; this influx of nutrients starts off the food chain. Plankton and krill get eaten by anchovies, sardines, mackerel and other ‘bait fish’, which are eaten by pelagic game fish, pelagic birds, and of course Pinnipeds (Seals), Dolphins and Whales.